International Journal of Labour Research • Volume 11, Issues 1-2 (2022)

New wine in old bottles:

organizing and collective

bargaining in the

platform economy

Agnieszka Piasna

Senior researcher, European Trade Union Institute, Brussels, Belgium

Wouter Zwysen

Senior researcher, European Trade Union Institute, Brussels, Belgium

36

International Journal of Labour Research • Volume 11, Issues 1-2 (2022)

New wine in old bottles: organizing and collective bargaining in the platform economy

Introduction

Digital labour platforms are at the centre of the debate about the future of work, owing to

their role in advancing the use of digital technologies in mediating and organizing work.

Automation of organizational functions and online labour intermediation have expanded

the pool of available workers beyond geographical or organizational boundaries and

have radically transformed existing business models, jobs and the way work is organized,

challenging the relevance of existing ways of ensuring good working conditions and

income (Drahokoupil and Piasna 2017; Vallas and Schor 2020; Graham, Hjorth, and

Lehdonvirta 2017). In this context, maintaining social dialogue and organizing online gig

(platform) workers represent major challenges. Moreover, digital labour platforms are

pioneering solutions in terms of algorithmic management, digital surveillance, remote

work and cross-border outsourcing, which are increasingly being adopted in the oine

economy. Developments in the platform economy are thus crucial in providing lessons for

collective interest representation and mobilization in changing labour markets. There is a

need to examine the strategies adopted by trade unions to face these challenges in order

to offer recommendations for future action.

This article addresses these issues by exploring the concerns that trigger the resistance of

workers in the platform economy, as well as their attitudes towards collective organizing

and the tactics they pursue when resisting the practices of online platforms. To better

convey the signicance of the platform economy for the wider world of work, we position

it within broader trends towards the development of internet-based labour markets and

the adoption of digital technologies for organizing and managing work across various

traditional sectors. The article presents a non-exhaustive review of recent forms of

organizing and mobilizing platform workers across Europe, with the objective of mapping

current variations in trade union strategies towards technological change and analytically

distinguishing emerging patterns in representation forms among the platform workforce.

Internet-based world of labour

Digital technologies have ushered in profound changes in the organization of work and

employment. The technology-mediated matching of labour supply and demand has created

online labour markets where jobs across different skill levels are divided into assignments,

ranging from micro-tasks to larger gigs, and then commissioned virtually to workers who

are often considered to be independent contractors. Digital labour platforms are at the

forefront of these changes. These economic agents provide digital infrastructures that

greatly reduce the transaction costs involved in matching work with workers on an ad

hoc basis and that defy boundaries. Deployment of algorithmic management and digital

surveillance, aimed at increasing eciency in task performance, have generated a host

of challenges related to, for example, biases and information asymmetries due to the

automation of managerial and human resources functions, data protection and the use of

intrusive surveillance technologies (Drahokoupil and Piasna 2017; Prassl 2018).

37

International Journal of Labour Research • Volume 11, Issues 1-2 (2022)

New wine in old bottles: organizing and collective bargaining in the platform economy

Much ado about nothing? The size and impact of

platform work

The novelty of the technological solutions deployed by platforms and, perhaps more

importantly, their impact on working conditions has generated a wide policy debate and a

boom in research. The actual size of the platform workforce is less impressive, even though

there is little agreement on this issue, given that this phenomenon escapes most established

labour-market statistics (see discussion in Piasna 2020). Recent cross-national data from the

representative European Trade Union Institute (ETUI) Internet and Platform Work Survey

(IPWS), carried out in 2021 across 14 European Union (EU) countries, suggest that 4.3 per

cent of the working-age population had worked on platforms in the previous year (Piasna,

Zwysen, and Drahokoupil 2022). Earlier estimates from the COLLaborative Economy and

EMployment (COLLEEM) studies of the European Commission put that number at 8.6 per

cent (Urzí Brancati, Pesole, and Férnandéz-Macías 2020), with this higher value explained by

the strategy of sampling internet users who sign up for online panels. The ETUI IPWS shows

us that only about 1 per cent of Europeans rely on platform work for the majority of their

income.

Nevertheless, the still-modest size of the platform workforce should not lead to a dismissal

of its signicance. First, the internet-based world of labour is much broader than digital

labour platforms alone. The ETUI IPWS attempted to measure this wider phenomenon,

referred to as “internet work”, by looking at various ways of generating income on the

internet on a freelance basis, using apps or websites that organize the exchange but which

do not necessarily have all the features of labour platforms, such as developed rating

systems or payment processing mechanisms. The results show that an astounding 17 per

cent of Europeans did internet work over the past 12 months, while 29.4 per cent have tried

it at some point (gure 1).

Note: Average across 14 EU countries (Austria, Bulgaria, Czechia, Estonia, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland,

Italy, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Spain). All working-age adults.

Source: ETUI IPWS Spring 2021.

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Main

platform

workers

1.1%

Platform

not

main

3.2%

Internet

not

platform

12.6%

Internet

work

in the past

12.4%

Never done internet work

70.6%

Platform workers 4.3%

Internet workers 17%

Ever tried internet work 29.4%

%

1.1 3.2 12.6 12.4 70.6

X Figure 1. The size of the internet-based world of labour in Europe

38

International Journal of Labour Research • Volume 11, Issues 1-2 (2022)

New wine in old bottles: organizing and collective bargaining in the platform economy

This points not only to the scale of online labour markets, but also to the signicant

potential of further expansion for labour platforms, whose steady growth has already been

documented (Prassl 2018; Urzí Brancati, Pesole, and Férnandéz-Macías 2020).

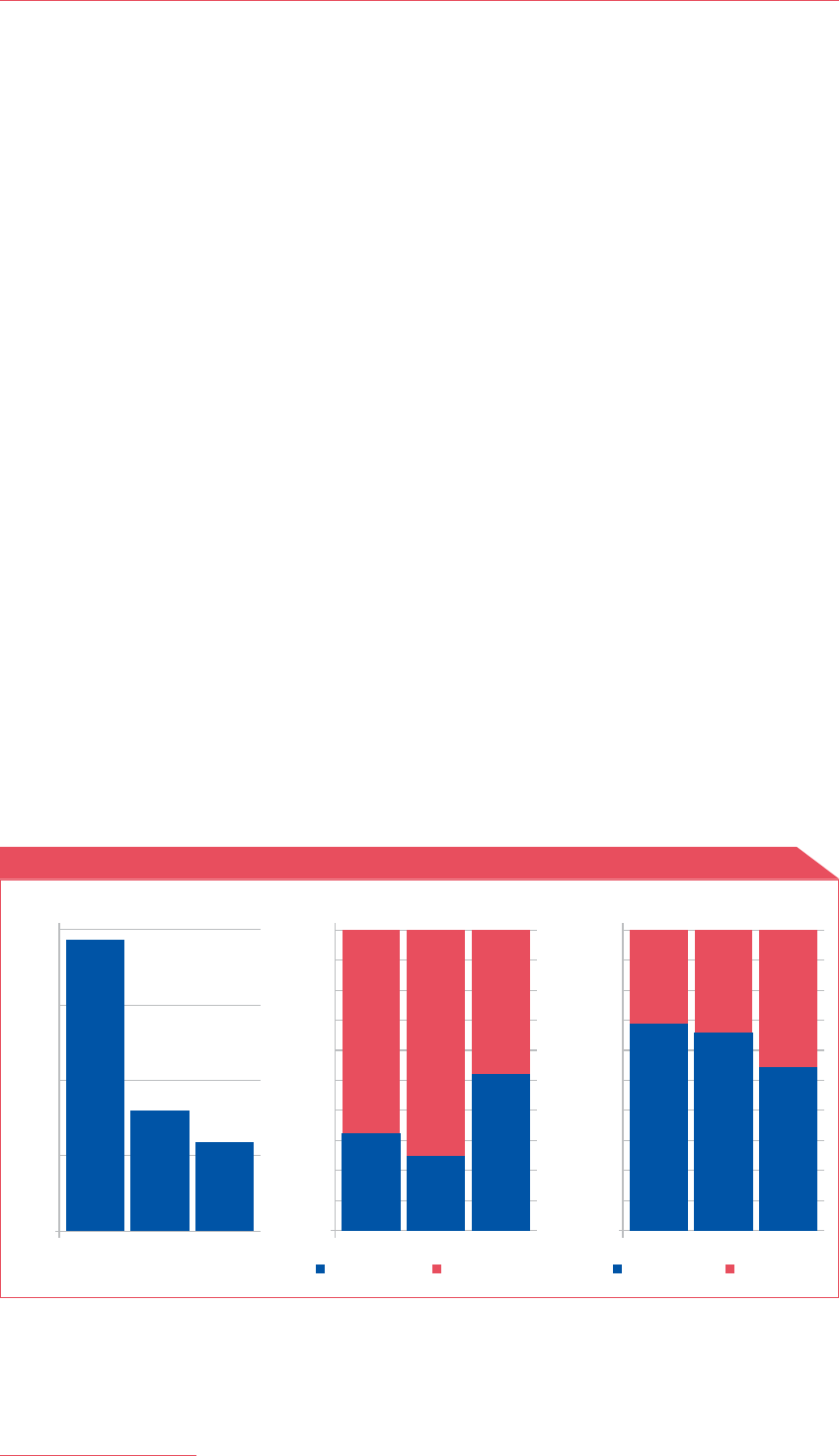

The growth potential varies by type of platform work, based on the types of task and the

location of the work. As shown in the left-hand panel of gure 2, services provided remotely

are the most common type of internet work in the EU, with only about one third of them

provided through actual labour platforms. On-location work, where labour matching is done

online but work is provided oine, such as handyperson work, tutoring or childminding, is

done by around 3 per cent of the working-age population and organized by labour platforms

for only one in four internet workers. The type most saturated by platforms is transport,

including both delivery and taxi services. According to the ETUI IPWS data, around one half

of drivers rely on labour platforms for their orders, while the rest are freelance, using other

internet-based tools to nd clients. AssoDelivery, an Italian industry association of food delivery

platforms, estimates that currently only about 11 per cent of food delivery is organized online,

with the remainder (89 per cent) receiving orders via traditional oine channels.

1

Besides being exemplied by the number of workers doing internet work not yet organized

through platforms, the growth potential of online labour markets is also evidenced by the

number of new entrants. The right-hand panel of gure 2 shows that, depending on activity,

between one third and one half of all platform workers started this type of work only in

the 12 months preceding the survey, that is in spring 2020 (see also Drahokoupil and

Piasna 2019). Thus they have done this work for less than a year.

Note: The left-hand panel shows the share of the working-age population doing internet work. The middle panel

shows the share of internet work that is carried out through online labour platforms. The right-hand panel shows

platform workers by the time they started this type of work. “Remote” work includes clickwork and professional

creative work; “on location” includes services such as handyperson work, childminding and tutoring; and “transport”

includes taxi and delivery work. Estimates are weighted.

Source: ETUI IPWS Spring 2021.

1

See https://assodelivery.it/settore/.

Internet workers

0

2 4 6 8

Share of working-age population (%)

Remote On-locationTransport

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Share of platform workers (%)

Remote On-location Transport

Less than a year A year or longer

Time since starting platform workPlatform workers among internet workers

0 10

20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Share of internet workers (%)

Remote On-location Transport

Labour platforms

Other internet work

X Figure 2. The growth potential for different types of platform work

39

International Journal of Labour Research • Volume 11, Issues 1-2 (2022)

New wine in old bottles: organizing and collective bargaining in the platform economy

Finally, the platform economy can be seen as a most extreme form of trends that are

also spreading to the traditional economy. Traditional companies implement some of

the platforms’ practices in managing their own workforces, such as tight monitoring and

control of workers through algorithmic management, data gathering and the optimization

of work processes. Moreover, implementing the platforms’ model of delegating tasks to

independent providers leads to a greater dispersion and fragmentation of the workforce

through remote work and outsourcing (Kilhoffer, Lenaerts, and Beblavý 2017; Prassl 2018;

Sundararajan 2016). These practices, especially when coupled with regulatory arbitrage,

can accelerate the race to the bottom in terms of labour standards and economic risks

assumed by workers, creating unfair competition with companies that do not circumvent

labour regulations.

All the above points explain current policy in relation to and research attention on the

platform economy. A better grasp of this work model can provide directions for dealing

with the future challenges facing an increasing segment of the workforce.

New and old sources of protest

When considering the prospects for social dialogue and collective representation in the

platform economy, or online labour markets more broadly, it is vital to understand the

concerns that trigger workers’ resistance and protest. Technological intermediation

introduces many new elements into the organization of work, but has it fundamentally

transformed workers’ preferences and demands, and – by extension – required a redenition

of unions’ approaches and their focus?

Certainly, technological change breeds novel challenges, notably related to digital

intermediation and algorithmic management offering new scope for control and

surveillance. Vandaele (2018) highlights the health and safety risks augmented by digitalized

management methods and the lack of transparency regarding surveillance practices

and opaque rating and task allocation systems – all contested and resisted by platform

workers. However, most of these grievances come down to traditional conicts over power

and information asymmetry, whereby decisions are taken unilaterally, often under the veil

of algorithms, accompanied by a lack of channels to appeal unfair decisions (Wood et al.

2019; Lehdonvirta 2016). Some of the novel features of platform work advertised as its

main advantages, notably extreme working time exibility, are also resisted by workers,

who show a preference for more predictable, regular hours with stable income (Piasna and

Drahokoupil 2021).

Many of the employment and organizational practices of platforms – such as home-based

production, piecework payment and subcontracted work – all date back to the early era of

industrial capitalism (Joyce et al. 2020; Prassl 2018; Stanford 2017). For the most part, these

practices are an extension of a move towards the recommodication of labour, where the

risks and costs are shifted to workers (Piasna 2022). The perceived novelty of platforms as

40

International Journal of Labour Research • Volume 11, Issues 1-2 (2022)

New wine in old bottles: organizing and collective bargaining in the platform economy

technological start-ups thus hides vulnerabilities that are the same as those found in other

forms of precarious labour.

Demands and conicts over distributional issues thus take centre stage, and this situation

is supported by the empirical evidence. The Leeds Index of Platform Labour Protest nds

pay to be by far the most common cause of labour unrest globally (Joyce et al. 2020).

Workers contest non-payment and very low payment, a heavy load of unpaid labour,

income insecurity and a lack of compensation for work equipment (Pulignano et al. 2021;

Drahokoupil and Piasna 2019). Vandaele, Piasna and Drahokoupil (2019) showed the

centrality of distributional issues among Deliveroo riders in Belgium who joined the SMart

cooperative to access minimum wage provisions and a compensation scheme, and who

protested when this arrangement was terminated.

In Europe, and across the global North, the second most widespread cause of dispute is

employment status (Joyce et al. 2020). The common practice among platform companies

of classifying their workforce as self-employed workers or independent contractors has

immediate consequences in terms of access to labour rights and protections, and is also

the primary obstacle to unionization (Gebert 2021; Vandaele 2018). Organized activity

undertaken by self-employed workers and freelancers can be considered a breach of

competition rules, effectively depriving platform workers of access to fully edged collective

bargaining and freedom of association (Johnston and Land-Kazlauskas 2019).

Attitudes and experiences among platform workers

The grievances of platform workers resonate with long-standing labour demands, but is

there something essentially novel about the workers engaged in this type of work? Do

platforms recruit from a specic demographic group, and what do we know about attitudes

towards collective organizing? Existing research shows that unionization among platform

workers is generally quite low, but their attitudes towards and propensity to engage in

collective action can be related to their demographic and socio-economic characteristics.

In an in-depth study of Deliveroo workers in Belgium, Vandaele, Piasna and Drahokoupil

(2019) found that riders did not generally hold negative views towards unions, nor did they

consider unions incompatible with platform work. Their views were thus not essentially

different from those of their peers in the traditional labour market. Importantly, riders were

more likely to want to join a trade union the worse they experienced job quality in terms of

economic security, autonomy over their work and enjoyment at work.

The ETUI IPWS highlights that, while there are important differences in socio-demographic

characteristics, platform workers are essentially not radically different from the oine

labour force when similar types of activities are compared (Piasna, Zwysen, and

Drahokoupil 2022).

41

International Journal of Labour Research • Volume 11, Issues 1-2 (2022)

New wine in old bottles: organizing and collective bargaining in the platform economy

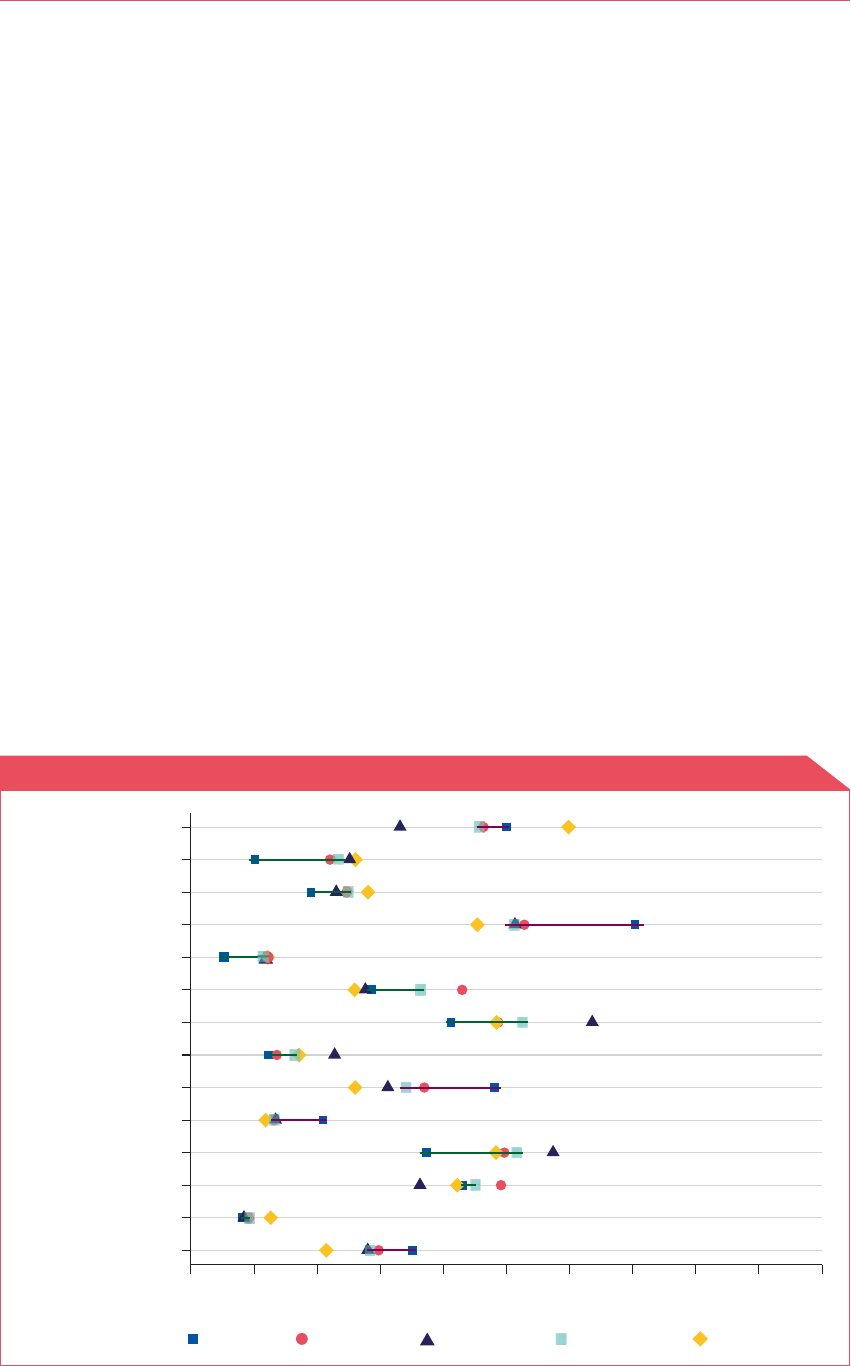

Figure 3 highlights how platform workers overall differ from the oine labour force, and

how different types of platform worker differ from each other. On average, more men than

women are platform workers, but this differs greatly by the type of platform work, with

60 per cent of on-location workers being women, compared with only about one third of

drivers. There are rather more young people among platform workers, but about one half

are aged 35 years or older. Only a small minority of platform workers are students, although

their share is slightly higher than among oine workers. Remote platform workers, unlike

on-location workers, are more likely to have university qualications. Platform workers

more often live in big cities, especially drivers, as this is where the work is available. Platform

workers are also more likely to be foreign-born, likewise particularly drivers. These socio-

demographic characteristics indicate a lower exposure of platform workers to traditional

trade unions.

Platform workers who are also employed in the oine economy are more likely to work on

a temporary or self-employed basis than to work as employees; this difference is even larger

for on-location workers. When looking at their main activity, platform workers are less likely

to work in traditional industries and more likely to work in the service sector. This all results

in lower rates of platform workers reporting a trade union at their workplace, particularly in

the case of on-location workers.

Note: The gure shows the weighted shares of dierent types of platform workers and oine workers, by socio-

demographic characteristics and the characteristics of their work in their main paid job. The line indicates whether a

characteristic is more (green) or less (red) common among platform workers than oine workers.

Source: ETUI IPWS Spring 2021.

Trade union at work

Elementary occupations

Professional/managerial

Private services

Industry and construction

Employees–open-ended

Foreign-born

Live in a big city

University qualifications

Students

Age: 35+

Age: 25–34

Age: 18–24

Women

Share (%)

Offline workers All platform workers

Platform: remote Platform: on-locationPlatform: transport

010203040506070 80 90 100

X Figure 3. Characteristics of platform workers

42

International Journal of Labour Research • Volume 11, Issues 1-2 (2022)

New wine in old bottles: organizing and collective bargaining in the platform economy

Organizing and mobilizing platform workers in Europe

Thus far, labour protest in the platform economy has unfolded along several convergent

lines and logics of action, despite the considerable heterogeneity of platforms and types of

work. Early actions have overwhelmingly been of a bottom-up nature, with workers within

the same platform uniting over contentious issues in ad hoc strikes, demonstrations or

online campaigns (see Johnston and Land-Kazlauskas 2019). As the platform workforce

is digitally managed, and thus constantly connected, online channels of communication

such as forums, chats or social media groups have proved effective in exchanging views,

formulating demands and mobilizing atomized workers. Many of these initiatives have

morphed into grassroots organizations led by fellow workers and focused primarily on

increasing the membership base (Vandaele 2018).

While the availability of online channels of communication is key in all types of platform

work, given the absence of a shared physical workplace, the potential for forging collective

identity and solidarity is augmented by geographical proximity and opportunities for

personal meetings, as well as company identity via the visible branding of work gear. These

conditions are easier to full in on-location platform work with services delivered in public

spaces, notably transport and delivery. This is reected in the emergence of multiple worker-

led initiatives in this sector, such as Collectif des coursier-e-s in Belgium, Collectif Coursiers

Bordeaux in France and Liefern am Limit in Germany.

Remote platform work, as well as on-location work delivered in private spaces (e.g.

childminding) or purposefully hidden from public view (e.g. mystery shopping), lack many

of the features conducive to worker organizing found in transport and delivery. However,

online communication tools and charismatic leadership can be used to build community

groups worldwide among people who can only be reached online. An inspiring example

is YouTubers Union, founded in 2018 by a popular German content creator as a Facebook

group for people earning money by posting videos on YouTube who were dissatised with

the company’s pay policies.

The evolution of YouTubers Union into FairTube, since 2021 a formally registered

organization supported by IG Metall, is an emblematic further step for bottom-up

initiatives: gaining legitimacy and bargaining power through recognition and support

from mainstream unions, as well as institutionalized forms of association. Building

alliances between worker-led initiatives and unions shows the potential for innovation and

experimentation going beyond the renewal of traditional organizing capabilities (Gebert

2021). Such efforts can include the provision of a structured network of support, expertise

and material resources. Platform workers can be further integrated in insurgent unions

specic to the platform economy (such as the App Drivers and Couriers Union, which started

out as an association and was later incorporated as a branch of the Independent Workers’

Union of Great Britain) or the sector-specic arms of some mainstream unions (such as 3F

Transport in Denmark; the transport section of the Swedish Trade Union Confederation;

the Food, Beverages and Catering Union in Germany; and the hospitality division of the

43

International Journal of Labour Research • Volume 11, Issues 1-2 (2022)

New wine in old bottles: organizing and collective bargaining in the platform economy

largest Dutch union, the Federation of Dutch Trade Unions).

2

These strategies can build

on experiences with mobilizing non-standard workers, such as opening up membership

to solo self-employed workers or particular occupational groups, such as artists.

Trade unions defend platform workers’ interests by leveraging power in relation to

other stakeholders, in line with the logic of inuence as postulated by Vandaele (2018).

In that sense, the emergence of legitimate actors on both sides of the negotiating table

can facilitate collective agreements and deals. Employer organizations that group online

platforms can be helpful in settling sectoral or multi-company agreements, as opposed to

more fragmented rm-level bargaining, thus extending coverage. For instance, negotiations

between 3F Transport and the Danish Chamber of Commerce established a national sectoral

agreement for delivery riders for 2021–23, with the potential to cover multiple platforms.

A growing number of national collective agreements negotiated by unions with these

high-tech multinationals testies to the ecacy of “old” instruments. Nevertheless,

experimentation has been introduced in the form of, for example, cross-border agreements,

such as those between German-based Delivery Hero and the European Federation of Food,

Agriculture, and Tourism Trade Unions in 2018, establishing an SE (Societas Europaea –

European Company) works council with representatives from each European country where

the platform operates.

Trade unions have also tended to engage in legal action which, in most cases, is related

to the employment status of platform workers. Litigation is more widespread in countries

where there are important gains regarding minimum wages, paid leave and other

protections attached to achieving legally recognized employment status, as well as where

it is a prerequisite for entering formal negotiations (Vandaele 2018; Johnston and Land-

Kazlauskas 2019). Legal challenges can generate leverage over platforms especially where

workers’ bargaining power is too low to pursue other routes, but also where new provisions

specic to platform work have been introduced, such as the so-called “Riders’ Law” in Spain

(Law 9/2021), and where platforms are failing to comply.

Despite many successes of platform workers and their associations in winning legal battles,

the legal route has its limits in that judgments may conict, yield different outcomes in

different jurisdictions or be appealed, which increases uncertainty for workers. In that

respect, international labour standards and regulation of the platform economy have the

potential to provide a more coherent and consistent reference for national policies across

different jurisdictions, especially in view of the cross-border activity of many platform

companies. This direction has been pursued at EU level – although, admittedly, it does not

yet encompass all aspects of decent working conditions – with a proposed directive on

improving conditions in platform work.

2

Many examples of organizing cited here are described in more detail in the Digital Platform Observatory

(https://digitalplatformobservatory.org/), a joint initiative of the European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC)

Brussels, Belgium, the Institut de recherches économiques et sociales, Noisy-le-Grand, France and Association

ASTREES, Paris, France, funded by the European Commission.

44

International Journal of Labour Research • Volume 11, Issues 1-2 (2022)

New wine in old bottles: organizing and collective bargaining in the platform economy

Conclusions

The brief overview presented in this article clearly shows that trade unions, and industrial

relations systems more generally, have been changing and adapting to new labour-market

players, such as online labour platforms, and to new organizational practices (Hayter,

Fashoyin, and Kochan 2011). On various occasions, online platforms have demonstrated

a reluctance to enter negotiations with workers where they were not formally organized

or institutionally supported, yet various barriers, including employment status and the

atomized character of this volatile workforce, hamper long-standing strategies for building

a membership base in the digital economy. Traditional labour unions have thus been

deploying existing resources and organizational capacities to form novel networks

and alliances, rightly recognizing that, despite the increasing diversity of issues on the

bargaining agenda brought by technological developments, the core of the platform

workers’ struggle remains those issues that have continually taken the centre stage of

collective bargaining: fair pay, decent working time, social protection and labour rights.

Organizational experimentation has opened access to collective bargaining for platform

workers across a variety of sectors and jurisdictions, demonstrating that a synergy between

“the organisational capacity of the ‘old’ and the imaginative spontaneity of the ‘new’” (Hyman

and Gumbrell-McCormick 2017, 557) is an effective way to resist the recommodication of

labour in the platform economy.

Lessons for collective representation of platform workers learned from the European

context include the following:

8

focusing on long-standing labour demands, such as decent pay, health and safety, non-

discrimination and working time, thus recognizing commonalities between platform

work and other forms of precarious labour;

8

forming novel networks and alliances with emerging associations and bottom-up

initiatives;

8

deploying digital communication tools in reaching a dispersed yet constantly connected

online workforce;

8

developing social dialogue, with a focus on multi-employer and sectoral bargaining; and

8

leveraging institutional inuence before expanding the membership base.

In addition to generating new forms of collective representation, unions have acted to

demand an appropriate regulatory framework for online-based labour. While national-level

initiatives to review labour law, such as those undertaken in Croatia and Ireland in 2021,

cannot be underestimated, greater impact could be achieved with international regulation

and standards. A prominent initiative is the lobbying effort undertaken at European level by

the ETUC for a regulatory framework governing the platform economy. Here, the legislative

process is already quite advanced: the European Commission published a proposal for a

directive on improving conditions in platform work in December 2021.

3

Apart from acting on

3

See https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/documents-register/detail?ref=SWD(2021)397&lang=en.

45

International Journal of Labour Research • Volume 11, Issues 1-2 (2022)

New wine in old bottles: organizing and collective bargaining in the platform economy

the key issue of employment status, the proposal recognizes the importance of establishing

a communications infrastructure for workers through channels not monitored by the

platform. Together with the increased transparency of this segment of work and worker

representation rights, this is an important step towards independent, collective worker

organization and representation in the internet-based world of labour.

References

Drahokoupil, Jan, and Agnieszka Piasna. 2017. “Work in the Platform Economy: Beyond

Lower Transaction Costs”. Intereconomics: Review of European Economic Policy 52 (6):

335–340.

———. 2019. “Work in the Platform Economy: Deliveroo Riders in Belgium and the SMart

Arrangement”, Working Paper 2019.01. Brussels: ETUI.

Gebert, Raoul. 2021. “The Pitfalls and Promises of Successfully Organizing Foodora Couriers

in Toronto”. In A Modern Guide to Labour and the Platform Economy, edited by Jan

Drahokoupil and Kurt Vandaele, 274-289. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Graham, Mark, Isis Hjorth, and Vili Lehdonvirta. 2017. “Digital Labour and Development:

Impacts of Global Digital Labour Platforms and the Gig Economy on Worker

Livelihoods”. Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research 23 (2): 135–162.

Hayter, Susan, Tayo Fashoyin, and Thomas A. Kochan. 2011. “Review Essay: Collective

Bargaining for the 21st Century”. Journal of Industrial Relations 53 (2): 225–247.

Hyman, Richard, and Rebecca Gumbrell-McCormick. 2017. “Resisting Labour Market

Insecurity: Old and New Actors, Rivals or Allies?” Journal of Industrial Relations 59 (4):

538–561.

Johnston, Hannah, and Chris Land-Kazlauskas. 2019. “Organizing On-Demand:

Representation, Voice, and Collective Bargaining in the Gig Economy”, Conditions of

Work and Employment Series 94. Geneva: ILO.

Joyce, Simon, Denis Neumann, Vera Trappmann, and Charles Umney. 2020. “A Global

Struggle: Worker Protest in the Platform Economy”, Policy Brief 2020.02. Brussels:

ETUI.

Kilhoffer, Zachary, Karolien Lenaerts, and Miroslav Beblavý. 2017. “The Platform Economy

and Industrial Relations: Applying the Old Framework to the New Reality”. CEPS

[Centre for European Policy Studies] Research Report, No. 2017/12.

Lehdonvirta, Vili. 2016. “Algorithms That Divide and Unite: Delocalisation, Identity and

Collective Action in ‘Microwork’”. In Space, Place and Global Digital Work, edited by

Jörg Flecker, 53–80. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Piasna, Agnieszka. 2020. “Counting Gigs. How Can We Measure the Scale of Online Platform

Work?”, Working Paper 2020.06. Brussels: ETUI.

———. 2022. “Precariousness in the Platform Economy”. In Faces of Precarity: Critical

Perspectives on Work, Subjectivities and Struggles, edited by Joseph Choonara, Renato

Miguel Carmo, and Annalisa Murgia. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

46

International Journal of Labour Research • Volume 11, Issues 1-2 (2022)

New wine in old bottles: organizing and collective bargaining in the platform economy

———, and Jan Drahokoupil. 2021. “Flexibility Unbound: Understanding the Heterogeneity

of Preferences among Food Delivery Platform Workers”. Socio-Economic Review 19 (4):

1397–1419.

———, Wouter Zwysen, and Jan Drahokoupil. 2022. “The Platform Economy in Europe:

Results from the Second ETUI Internet and Platform Work Survey (IPWS)”, Working

Paper 2022.05. Brussels: ETUI.

Prassl, Jeremias. 2018. Humans as a Service: The Promise and Perils of Work in the Gig Economy.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pulignano, Valeria, Agnieszka Piasna, Markieta Domecka, Karol Muszyński, and Lander

Vermeerbergen. 2021. “Does It Pay to Work? Unpaid Labour in the Platform Economy”.

Policy Brief 2021.15. Brussels: ETUI.

Stanford, Jim. 2017. “The Resurgence of Gig Work: Historical and Theoretical Perspectives”.

The Economic and Labour Relations Review 28 (3): 382–401.

Sundararajan, Arun. 2016. The Sharing Economy: The End of Employment and the Rise of Crowd-

Based Capitalism. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Urzí Brancati, Maria Cesira, Annarosa Pesole, and Enrique Férnandéz-Macías. 2020. “New

Evidence on Platform Workers in Europe. Results from the Second COLLEEM Survey”.

Luxembourg: Publications Oce of the European Union.

Vallas, Steven, and Juliet B. Schor. 2020. “What Do Platforms Do? Understanding the Gig

Economy”. Annual Review of Sociology 46: 273–294.

Vandaele, Kurt. 2018. “Will Trade Unions Survive in the Platform Economy? Emerging Patterns

of Platform Workers’ Collective Voice and Representation in Europe”, Working Paper

2018.05. Brussels: ETUI.

———, Agnieszka Piasna, and Jan Drahokoupil. 2019. “‘Algorithm Breakers’ Are Not a

Different ‘Species’: Attitudes towards Trade Unions of Deliveroo Riders in Belgium”,

Working Paper 2019.06. Brussels: ETUI.

Wood, Alex J, Mark Graham, Vili Lehdonvirta, and Isis Hjorth. 2019. “Good Gig, Bad Gig:

Autonomy and Algorithmic Control in the Global Gig Economy”. Work, Employment

and Society 33 (1): 56–75.